According to completely sound advice, a good way to make anything compact and meaningful is to make sure everything has a purpose. Good writing employs every character, moment, and scene to the benefit of the larger story. Good filmmaking involves making good use of color, frame, and audience point of view to keep attention on the places most useful for the audience. Good game design shaves away bloat in the mechanics or UI so everything in the game and on the screen has a practical use, even when the game introduces more elements as it progresses. In short, excise excess, keep focus on core components, and keep the audience focus on pursuing the end goal.

In a lot of ways, I enjoy games that manage to employ these strategies well. Super Meat Boy is an example that has stripped away almost everything but the central mechanic, employs its soundtrack and aesthetic to keep the player’s energy high, gives almost tactile consequences to mistakes and mishaps, and everything in the design encourages the player to be on-task and forward. Games like Bastion use a full range of visual, story, narration, and soundtrack to make sure the story and the player develop in step with one another, and guides the player through new mechanics and story beat without flooding them. Games like these with tight design and effective stories are easy to love, for exactly the right reasons.

But I also like bad games.

Though perhaps that characterization is a little unfair. I like games that have bad elements. I like games that do things wrong, I like elements that stumble and hiccup and crash and grind to an uneasy stop. I like it when things are clearly made to be a certain way, succeed, shouldn’t be good, but work anyway. I like it when something is meant to do something, utterly fails, and ends up even more charming than if it had worked as intended. I like the odd occasions where missteps on producing the developer’s vision produce better outcomes. I like it when games do things badly.

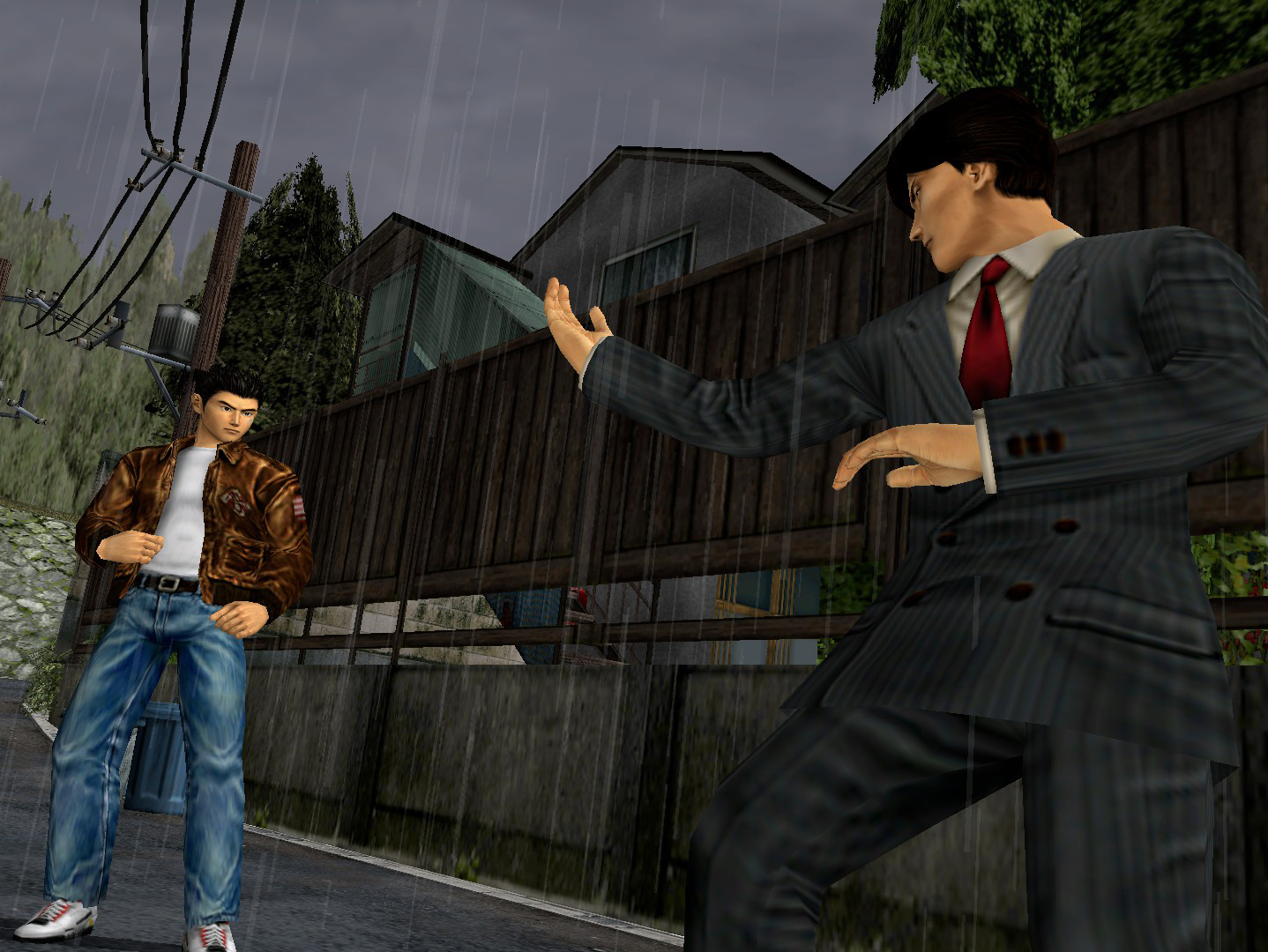

One of my favorite games is Shenmue, and it’s a game that is, by efficient design standards, absolutely awful. Ryo Hazuki lives in a rural Japanese village, in a town where everyone knows everyone, and starts his quest against everyone’s advice and honestly against good sense. From there, the player explores an utterly foreign area that Ryo knows very well. They speak to Ryo’s friends and neighbors like strangers, because they honestly don’t know any better, and they can’t. There’s no reason for his neighbors to give him a tour of his neighborhood, or explain which of the folks around town are Ryo’s friends, so nobody does. No one delivers exposition, so the player grabs the reigns of someone who knows their way around and instantly gets lost. The player and character are largely out-of-sync through most of the early game.

Beyond that, the game offers corner stores and shops that just sell stuff. Random things. Dried fish? Sure! Bag of chips? Help yourself! Some batteries? Why not! Vending machines dispense coffees or sodas. Most of these are not helpful; they don’t restore health, they don’t give buffs, sodas are instantly consumed and most of the other items just litter the inventory like so many random trinkets. Little capsule machines dispense toys that Ryo can collect. Getting all of them doesn’t unlock anything, nor do they really do much—Ryo can look at them, but that’s about it. Ryo can agree to help look after a kitten, who lives in a box at a nearby shrine. It never grows up or travels with Ryo. It’s just there, to be looked after and pet. There’s an arcade where Ryo can spend his money to play darts, or boxing games, or Space Harrier. There’s even a Sega Saturn in his living room, which you can play if you happen to win any games from raffles hosted by the corner shops.

I like games that do things wrong.

But I really like Shenmue, more or less for the reasons listed above. I find myself drawn to media that lets me breathe. There’s something about the metaphorical beat panel in life that makes everything so much more striking when things do happen. The moments of silence, the sitting, the long conversations with older gentlemen on park benches feel like moments I would treasure in my actual life, and often they’re moments that other games pad with dramatic soundtracks and as interludes to explosive setpieces. The contrast is compelling, but it’s not the only way to go quiet in games. Sometimes it’s okay to sit.

If I were to go back and play Shenmue right now, I have few doubts I would find it plodding and awkward. More than just the long, awkward pauses in dialog, I would also have to contend with a game world that doesn’t particularly have any interest in keeping an active pace. It feels like a little village, with its dirt roads to mountain subdivisions. Lots of gravel crunching underfoot down a mountain, where the main road transitions to jogging down slender streets packed with barbers and fast food shops.

When the game is actually on task, movement is awkward and slow. Ryo is unwieldy even at his most graceful. The Dreamcast’s single stick made it so the camera was controlled by triggers, which snapped the camera to whichever direction Ryo was facing. It’s fine enough as a control mechanic, but hardly as smooth as it could be if the camera’s turn would keep pace with Ryo. When Ryo turns around, the animation isn’t a smooth lean into a pivot, it’s an awkward shuffle in place that has him spin entirely without taking a step forward or backward, a motion that is perfectly doable but utterly alien. People almost never turn in place.

In combat, little ankle-high railings can lack Ryo in weird locations, or stuck in corners by random bits of debris. The player’s sense of self-control is lost trying to shuffle around geometry or get the exact angle for movement the current camera position to make dodging feel nature. Instead, players bumble into kicks by side stepping forward, or backing off from a big swing diagonally.

Each of these are aggravations that gaming has largely learned to avoid. Games have gotten to where they can animate models to stand on uneven ledges, or have players stumble and trip over little rocks or bars instead of coming to a dead-stop. Movement and camera are much better at working in concert, even without the need for a second stick.

And perhaps it’s just nostalgia, but I feel like Shenmue would lose something if it adopted these upgrades. The dialog, stilted and jittery as it is, would lose charm if it were made faster and punchier. The doddering of old men would feel impatience and hurried. Tighter design would carve away some of the excess, saving players time by freeing them from distraction. The arcade would become a fraction of its current form, and capsule toys would likely be removed entirely. Restaurants would sell health restoration in bento boxes and corner store batteries would be useful for reasons other than a single scene that benefits from a flashlight. It would, likely, look a lot more like Yazuka.

Which, in many respects, is a good game. But in so being, all of the pacing and atmosphere would get drowned in a slideshow of fistfights. Keeping the player engaged often means doing so at the expense of what grounds a scene. The contrast is lost, or at least greatly abbreviated.

Sometimes, I think I’d prefer the “bad” game. Not because tight design is bad, nor because a meandering pace is always good, but the joy of discovering something new is something that’s hard to replicate intentionally. Finding a bit of meditative joy in a game that’s full of fights in the parking lot and mystery ambushes in alleyways is a kind pleasure that’s as much a joy for the surprise as the experience itself. Sometimes it’s good to collect a bunch of figurines of Sonic the Hedgehog and a forklift. And sometimes it’s nice to pause a story of violence to listen to a tape you bought at the little shop up the street.

Then, when you get up to go get in a fistfight with a biker, you can return to the immediacy.

Taylor Hidalgo is a writer, editor, and friend enthusiast. If you want to hang out with him, you can find him on Twitter. If you want to support his passions, you can go give Haywire Magazine and Critical Distance a read!

Thoughts?