Written for Continue Play, recreated with permission.

There’s more to playing a game than simply gameplay.

Mechanics may structure a game, but graphics give it a face, and sound design and dialog give it a voice. Games aren’t simply in the playing and nothing else. Some may argue that a game’s first, foremost, and only really important metric may be the gameplay, but games have always flirted with reaching through the screen and manipulating the player directly. Either their feelings, their moods, or the amount of money that they put into a coin slot, games will always have an interest in reaching beyond the trappings of the screen, and influencing reality in a more tangible way.

In part, that’s because games are as much a plaything as they are an experience. While the tongue-in-cheek “Walking Simulator” tag on Steam may have merit in that criticism, it isn’t to say that games like those can’t exist outside of a traditional play structure. Almost for as long as there have been games, there have been experiments to alter them. Early horror games used pre-assembled filmed sequences to create narrative sequences and play environments, games like Dragon’s Lair were mildly interactive films at best, and Quantic Dream’s development strategy seems to be more rooted in experimenting with game technology and narrative than making games as they’re traditionally understood.

However, for as little as the above examples may seem like games to the casual eye, they’re still getting to the core of what games really are. They’re not just play things, although they have plenty of the curiosity inherent in play; they’re also play experiences.

As introspective and artistic as the word “experience” implies, it doesn’t necessarily have to be built onto a game that leans heavily on artful, indie, or artsy experience over the actual mechanical manipulation. Often, when the experience and aesthetic are built to compliment an already playful game, the feeling of play is magnified rather than diminished.

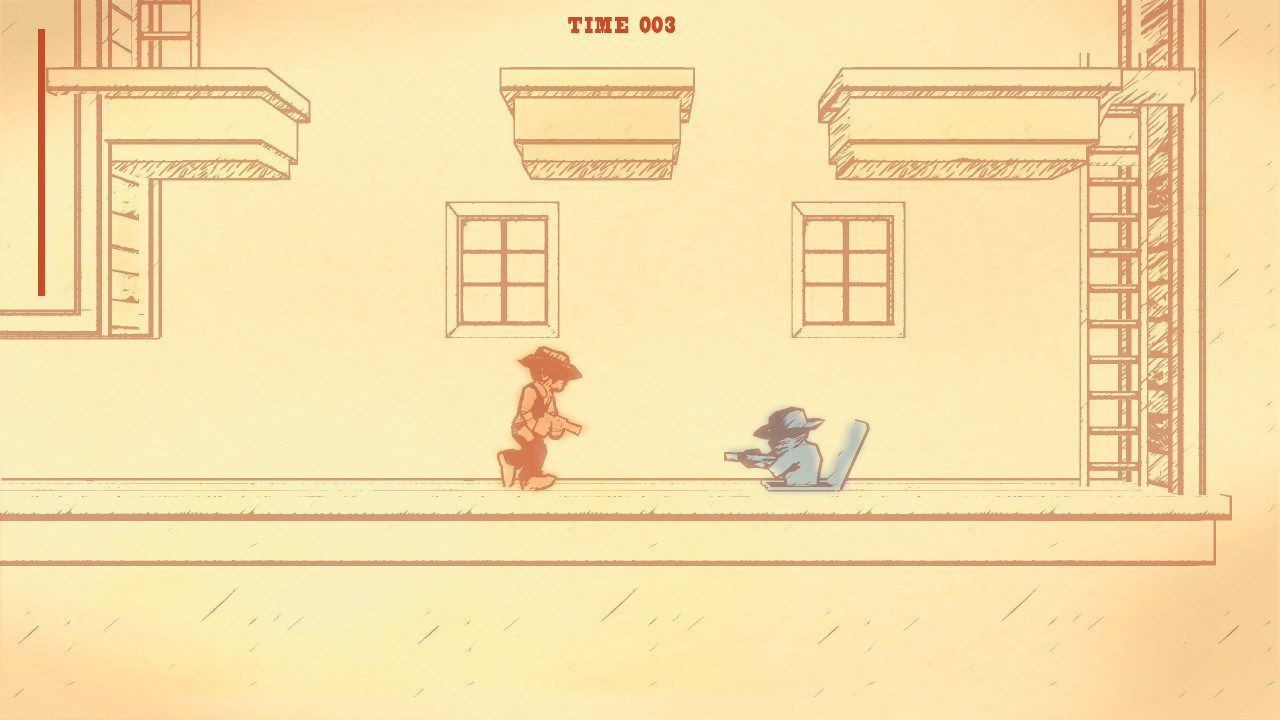

Gunman Clive is an example of a game that is better than just the base gameplay because of its experience. The faded sepia wash of the background material, simple shifting of the sketchy stage design, and an understated western soundtrack all bring more out of the game’s character than simple mechanics could by themselves. As an aesthetic, Gunman Clive is beautifully rendered, the soundtrack is cleverly applied, and the game feels wonderful in recollection. At a game engine and stage design level, Gunman Clive is barebones and direct. The action is smooth, feels a little too dated to be as polished as it should be, but is an accomplished -if brief – game.

Which isn’t to say the mechanics are bad. They borrow a lot from the games that came before them. The shooting and difficulty feel reminiscent of the Namco arcade Rolling Thunder; the platforming evokes memories of Metal Slug and Mario Bros. 2; but the aesthetic, tone, and soundtrack manage to feel simultaneously hauntingly familiar and brand new at the same time.

The soundtrack has the most to do with that, bringing with it countless memories of spaghetti westerns, old wild west shows, and the sense of oddball sincerity that accompanies the kidnappings, horse chases, and six shooters that follow in the wakes of cowboys and violence. More than just mechanics, the game seems to gel.

More than that though, Gunman Clive manages to assemble all of these aspects into a perfectly cohesive picture. Those who argue that games are art often point at games that make beautiful screenshots, and have gorgeous concept art. Games like Gunman Clive can’t make the same claims. The screenshots are generally too busy to be minimalist, but too sparse to be fully featured. In motion, Gunman Clive betrays a deeper and beautiful artistry. The foreground seems to breathe in motion: hatching shifts with the shadows, opponents pop into and out of cover, and its stages flow together to tell a story which feels naturally emergent despite highly different settings and set pieces being brought into play.

Gunman Clive is very much a visual and aural experience, in addition to also being a game. The actual gameplay is middling and as an experience it’s short – deserving of its low $1.99 price tag. But the way the entire experience comes together is something that makes it stick in the memory long after completion. Gunman Clive just wouldn’t be the same game without its aesthetic, or even a shadow of the same game.

There’s something entirely – and appropriately – Wild West about the whole experience: the sepia tone and shifting lines bringing back memories of Wanted posters, the sound of six-shooters firing and the distant-but-appreciable acoustic guitar all solidify that atmosphere. It may be a far cry from Unforgiven in tone – it’s closer to Wild Wild West in that regard; but it feels no less authentically Western.

Without that atmosphere, without the unwavering sense of unity between theme and cinema tropes, there would simply be a game. The gameplay would falter, the experience would be terminally lacking. Gunman Clive is made better by its aesthetic and atmosphere; without it, would only be defined by its shortcomings.

There’s more to playing than simply gameplay, and without acknowledging the importance of that distinction, Gunman Clive would be playable, but infinitely less playful.

Thoughts?