Written for Haywire Magazine.

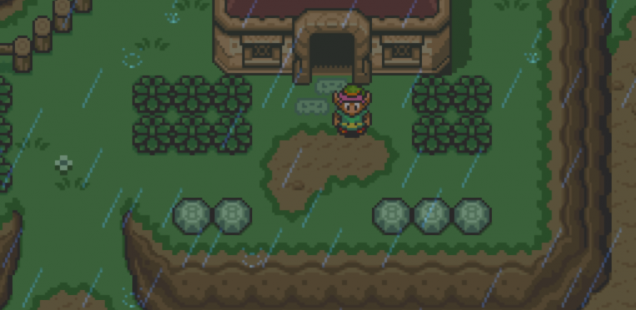

The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past begins in a thunderstorm. The peace of the night has been interrupted by peals of thunder; occasional cracks of lightning paint harsh whites against the interior stone before sinking back into shadows once again. Rain shatters against the windowpanes, coming apart in chaotic splatters against the windowsill.

As Link awakens, the cool interior warms with the orange glow of lantern light. The sconces on the wall bathe the interior in gentle, relaxing hues. Outside, the storm rages, but the occasional peals of thunder don’t disturb the serenity inside. Inevitably, Link must leave his home behind, and head out into the clattering rain. At almost no other point in the game is there ever the same sensation of warmth. There are respites from danger, but the house never truly feels like a home again.

“Home” is a difficult concept for a game to come to grips with. Games typically build experiences around mechanics: worlds to explore, enemies to conquer, points to capture, items to gather, or story beats to hit. Games communicate the idea of external conflict, or barriers of entry, or ways to make a single, finite experience engaging. They have physical spaces to emulate, and they have rooms to explore and objects to pick up, handle, and put down. Each room has a purpose, a hidden object, some NPC to communicate a story idea, or an in-joke a crafty developer left for his friends. There is rarely “nothing” in games. It’s hard to illustrate that featureless broom closets exist, doorways that lead to valueless places. Those are little nothings, but they’re valuable for that sense of home.

The nothings, the stories, the vignettes are actually the pieces of life that collect over time. They—far more than the drywall, studs, and shingles—are what make a house into a home. A photo album is only as good as the photos inside are meaningful. They can point to a fuller life, but it’s hard for them to really represent them without having some story behind them. The feeling of having a whole life woven into the very walls is a hard thing to show without also showing the whole life.

Nothingness is considered bad design. It’s hard to reasonably approach purposefully and meaningfully designing nothing for the sole benefit of subtle atmospheric cues. Like a chair that exists for no reason other than to be sat in, or a letter on a dinner table that turns out to be a credit card pre-approval notice simply because that’s the sort of suburban debris that accompanies a lot of dinner tables. They’re not useful. They don’t hold a secret purpose. It’s nothing but spam mail, a daily nuisance to be collected and torn up at some point, probably next Wednesday because the trash comes Thursday morning.

The precise nothingness needed to turn a house into a home can be different for every occupant, for every house, but it’s something that mechanics struggle to communicate. Old Marshalls catalogs and manila folders full of early childhood report cards are things that a home might have. They might point at a history of thousands of other envelopes that have come and gone through the rusting mailbox outside. Little chips in picture frames where hangings went less smoothly than everyone had planned. An old family reunion photo that never made its way to the photo retouchers in an envelope next to a yellowing stack of business cards. Telling a tenth of a story is something everyone’s home does eventually. Life accumulates these emotional receipts, like snapshots of a vacation taken with an Instagram filter set to the mundane. There’s a lot of nothing special in a home, but it all needs to be there for the place to become a home. Without, it’s just a house.

But, that history isn’t the sort of thing a game can easily address. Some games try, but without casual pointlessness, some of the warming comfort is lost. Games like Gone Home, built on the very homey aesthetic that games struggle to communicate, still feel too intentional. They are as precise as a director of photography’s framing shot. All the little notes nudge toward a story nuance. There are no red herrings, no smiley faces on report cards from younger times, no letters to read that point aimlessly into narrative voids. Details like these are all little but completed vignettes; all of it intentional. It’s a precision-engineered facsimile of middle America, but one devoid of that true homey nothingness.

In some games, players can accumulate enough gold, dollars, credits, or cash, and buy their own slice of real estate. Inside, these domiciles will frequently provide the player with ample storage, customizable furniture, places party members can congregate, or perhaps a place where the player can settle down and raise a family. The ability to customize the house to suit all kinds of tastes seems like it would promote the domestic bliss games are missing, but it’s hard to find a game that deploys these luxuries as much more than useful mechanics. Giving the player the ability to store items and party members provides a unified central hub, furniture gives an economy to crafters like carpenters and tailors, and raising a family means having a dating or romance aspect which carries longer term mechanical values. These things all make for good games, but they’re still functional. The Sims gives players total freedom to arrange their homes as they’d like, but there is objectively better furniture—more comfortable beds, higher entertainment televisions, better bladder control. While the player can make their home as much theirs as they’d like, the mechanics don’t want the players to exercise that freedom. The mechanics beg for players to have better things, not more likable ones.

“Home,” in games, is where players can go to recover their health between one dungeon run and the next. Home is where players can tell the game to save their file. Home is where the player passes the evening before the next day of farming. Home isn’t a place that’s ballooning with stories, contains multitudes of both comforts and aggravations, and a sense that the multitudes will happen again tomorrow, and the next day. A home is joy and mishaps, catastrophe and half-eaten tubs of ice cream, awful days followed by abysmal ones, and great days that end in termites. Homes are social, pragmatic, familiar, comforting, and completely unlikable.

Sadly, it’s hard for a house to become a home. No amount of matching furniture sets, well-placed narrative sticky notes, or strategically placed lighting cues can really communicate it. Games, for all the great that they are, aren’t good at making homes.

Once Link steps out, the warm home will be no more, and only mechanics will be left inside. Bright red mechanical benefits hidden in terra cotta. The warm, comforting glow of a place that shelters from the storm, where the player has meaningful and caring family connections, and which holds the protagonist’s whole life in pieces between four walls, that’s a fleeting instant, no more enduring than the flashes of lightning outside. Homes are where the hearts are, and nothing more.

More nothings, perhaps, would’ve been more homey.

Thoughts?