The specimen creep up in tight bunches in Killing Floor 2, lurching into dedicated fire. The onslaught of bullets ambushes them in doorways and windows. The group of soldiers, misfits, and manics defending their ground work with the precision of an oiled machine, with supporting fire during reloads and heals coming as quick as the damage. Everyone moves in synchronicity, as a single mass of gunfire and grenade.

A well-coordinated, well-equipped team is a nearly impossible challenge to surmount. A good plan, solid teamwork, and the right tools often makes the difference between success with no losses, and total abject failure with 100% casualty rate.

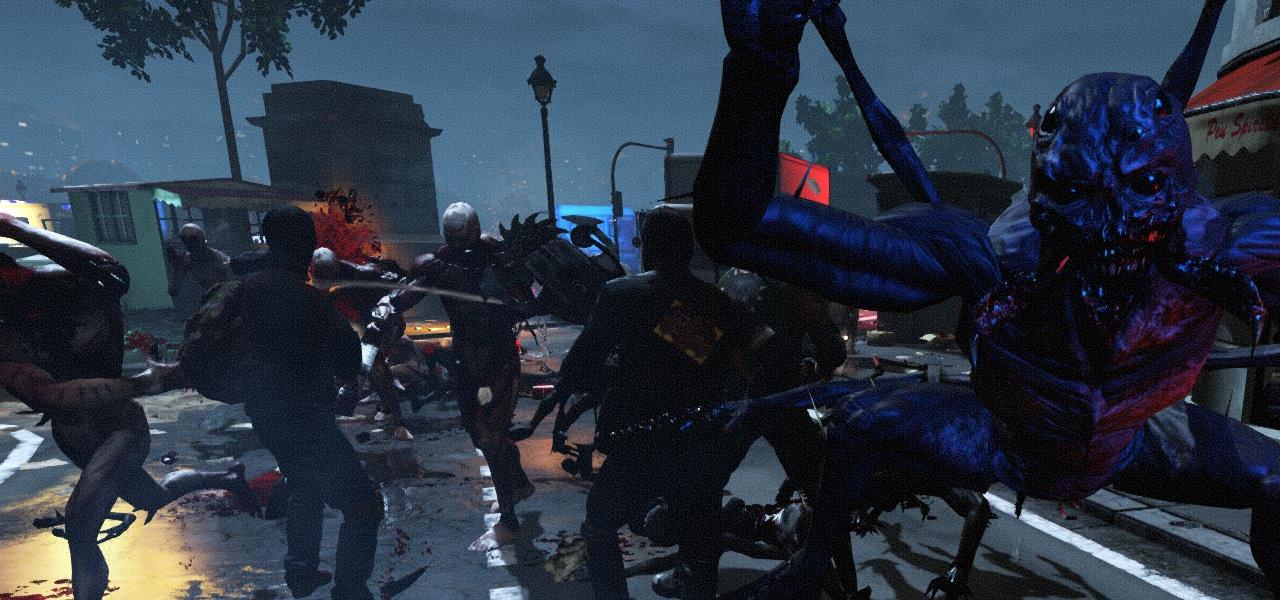

The larger zeds are much more threatening, charging through the bullets and blasts alike to tear into the mercenaries, scattering the ranks. Eventually, the hulking creature goes down, but the scattered team has to punch through the zeds that have surged in through the wake of the massive slabs of muscle and rage.

Once the coordination crumbles, the casualty rate starts to climb. Concentrated fire will fell most zeds as a matter of course, but as the players scatter, the fire becomes less dedicated. Without the layers of teamwork, each zed individually represents a more significant threat to the separated players. When the organization is lost, getting back to a stable team structure is its own nightmare scenario of blades, bullets, and blood.

An old adage in strategy is that plans never survive the first shot, but the concept is never illustrated more clearly than when tested. Especially in the chaotic combat. As little details start to come apart, and teamwork starts to crumble, any semblance of a plan crumbles at the seams. At least, in theory.

A good plan and a better team can see through wave after wave of almost anything, conquering conflicts almost by reflex, holding formation throughout. These are the sorts of teams for whom intricate plans are made. They can execute complex objectives, their communication is clear, and their tactical doctrine is cleverly executed. Watching such a team is something of a marvel, it’s striking to stand opposite a group so learned and capable that their sheer presence is itself a force of will. They are the kinds of groups the idea of morale was built upon.

I’ve never been in such a team. I’ve played around them, I’ve even been a member of their party as they run missions, but their unspoken and unstoppable synergy was something that remained foreign to me. Their plans, no matter how precise the expectation was, could always be met with respectable measures of success. Even when I personally failed, the additional objective of recovering from the fatal flaws I created with my bumbling was as smooth and effortless as the rest of their actions. It is a constantly humbling experience to be in such company.

When it comes to making plans, I’m as much an asset as anyone else. I have a mind for systems and structures, generally as much as any seasoned gamer, and my ability to formulate reasonable and respectable plans has never been an issue. Planning is something that I can reliably do.

Once it comes time to execute a plan, the pieces unravel. I train myself to be a steady hand with aim, to suppress panic when I’m faced with mortal danger, and to survive as best I can in a wide range of circumstances. This is true in survival horror, this is true in first-person shooting, and it’s likewise true in strategy games. No matter the situation, I’ll outfit myself to survive as best I can come hell or high water. Unfortunately, it also makes me a horrible teammate.

Teams are about trust and communication more than personal ability, and that is a metric that I will fail almost religiously. I have difficulty explaining abstract concepts succinctly, and that results in making me bad at communicating in panic situations. When I’m expected to swarm around my teammates during large encounters, I’ll instinctively navigate to the most open position, poised to flee at a moment’s notice. For my own survival, that’s a perfectly viable strategy, but for my team’s survival, that might mean putting the entirety of the enemies between us. If given the option of a high-risk rescue, or no-risk escape, I will unconsciously favor no-risk every time. Even when it means probably getting my team killed.

To me, the concept of a plan is an ideal: a theoretical perfection that rarely survives the first spanner in the gears. When the first things start to go awry, my reflex is to reposition, reconsider, and survive. I am a great survivalist, but I will invariably get everyone around me killed. For a plan, the various players must be as unlike me as possible. Plans may hardly survive the first shot, but even the best plan can’t survive players like me.

That said, I like plans. I like to consider, strategize, and contemplate how to best achieve success against unrelenting opposition. Plans are amazing to organize, and entirely magical to be a success.

They’ll always be alien to me, though. I’ve spent many, many hours training myself to be a solid survivalist, handy and capable even in dire straits. A good plan requires good teamwork in order to work the way it should. A plan accounts for variables by relying on the combined strength of everyone involved, I account for variables by putting myself in positions of least weakness. It seems we’re on opposite sides of the coin, I can’t help but feel like plans and I have never, nor will ever, see eye to eye.

So when the specimen close in, and the mercenaries scramble for footing against increasingly dangerous masses, I’ll start backing further away. My teammates have turned into distractions, I start calculating: who can I save without putting myself at risk, what can I do to keep my favorable position. The last thing on my mind is what the plan says I should do. My teammates crumble over crushing waves of teeth, then the hungry eyes turn to me with predatory expressions.

So I do the only thing I can think of. I turn and run.

Written for Critical Distance's Blogs of the Round Table under the "Plans" theme. If this is up your alley, go give the other pieces a read.

Taylor Hidalgo never fails to plan, but almost always plans to fail. You can find more of his work here and his words on Twitter.

Thoughts?