Originally written for Haywire Magazine.

Taylor Hidalgo speaks too much, often saying not enough in the process.

There’s a lot about a game’s story in the details. The details are more than just the instance of a single story, also. A constructed world has so many unanswered questions in the cracks, the spaces between the narrative and the gameplay. This can be as small as the fleeing shadow of a graffiti artist, their paint can clattering to the ground as a squad car drifts by. It can be as innocent as a single sentence scribbled in marker where security cameras can’t see, or as grandiose as watching groups of people crumble a statue to the ground, metaphorically and effectively shattering a dictator across the pavement. The devil, they say, is in the details.

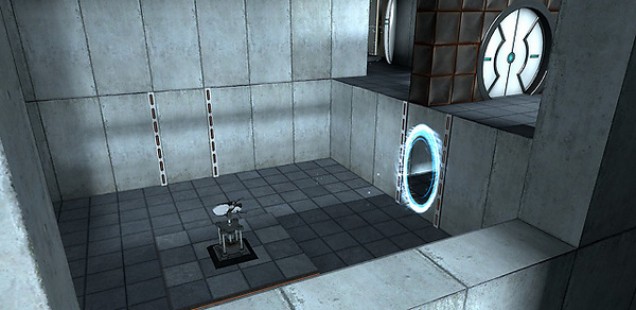

But sometimes, the details are the bigger story. Often conveying more nuance, and hints at further story mechanics in ways that dialogue or direct exposition cannot. The little details, the scraps of information and hints at deeper threads of narrative are the only interactions a player has sometimes with the larger world. Something as little as a single errant color betrays much more about the story than what the player or character understands. Valve’s Portal is very comfortable playing with this technique, where the first half of the game sets the stage with all the things not said. The disinterested voice of a cold and uncaring computer offers nothing for players to connect with. Instead, players find messages hidden from view, squirreled away in makeshift compartments behind the Enrichment Center’s paneling. The warm glow of internal lighting reveals these secrets to a player, showing as splashes of red against the too-sterile white of the test chambers.

Even in the latter half of the game, when GlaDOS speaks more as a character rather than a pre-recorded voice, her dialogue is still unique to her condition and the events the player inputs. GladDOS speaks, not in effort of delivering a story, but by being a part of one. Her conversations all speak to a here-and-now, and rarely explain anything seen previously. Her input is addressed directly to and about Chell, leaving the rich details of the world left to the eyes of the exploratory player, and almost none for those simply passing through. The grander story, the one involving Aperture Science, other test subjects, the universe, and why Chell is testing, is told exclusively in the abstract. You don’t read the story in a diary. You aren’t told what happens by an old acquaintance or passing exposition booth, as are the usual methods for delivering story. Instead, the details are all there for the player to find, just another detail in a sea full of stimulus, asking to be discovered and contemplated.

Further, when dialogue is employed as exposition, which only really happens at the distant end of Portal, it’s employed as taunting and teasing, used to leverage threats at Chell that also just happen to explain the universe, albeit indirectly. The purpose of the morality core, for example, was installed to prevent GlaDOS from filling the numerous chambers and hallways with toxins. This is alluded to briefly, with players passing an emergency phone at the entrance to her chamber, and driven home as a boss mechanic, although it does just as much telling a story. The numerous empty offices and hauntingly quiet corridors all promise a world the player isn’t informed of directly, but a world that the player knows and understands through context and convention. At least, to a degree.

This level of storytelling is among the strongest one can employ, even though it’s often the least direct. These are elements that are shown to the player rather than those told to the player. Scrolling introductory text or stated dialogue tends to produce a weaker connection to the material, giving a more vague and distant feeling to the events. What a player is shown, however, sticks with them. The subtle revelations and the silent reveals are often much more enduring, promising the player a world behind the edges they can see — even if it’s simply the hint of something just beyond the player’s reach.

This isn’t an all or nothing technique, though. Games like Bioshock, Borderlands, and the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. series do much in service of this, making an atmosphere rich with life, scenery, and style. Everything the player witnesses and experiences isn’t all there is to the world, and what goes on beyond the scope of the player is still as rich and varied as what the player experiences. It’s the promise of something bigger out there that gives life to numerous stories and creates the potential for much more than only what the player sees and hears.

In the first Bioshock, every scene is overflowing with detailed scenery, audio logs, and the frayed edges that distantly allude to the life that existed before. Borderlands, too, has such a busy interconnection of side quests and townships that it’s impossible not to imagine the sorts of stories that go on independently of the player input. In fact, we can see the lingering specter of stories untold in Borderlands. The S.T.A.L.K.E.R. games are practically an untapped goldmine of material, with each named and unnamed character presenting an opportunity for another perspective of the alienated zone. Or, at the very least, another reason for being there.

In particular, there’s something quietly rewarding about getting to explore a world that has as much nuance in the details as it has in the elements that directly influence the player’s pathway. Valve isn’t known for its non-linear approach to game design or the open-endedness of their worlds, but they are, for most purposes, full of life and teeming with narratives that have little more player interaction than a note scrawled hastily on the side of a building. Sometimes, these details are simply the quiet looks of desperation hidden behind seas of authority figures. But they matter. The breath of a story untold is easily something worth celebrating. There’s little else more satisfying than a story so delicately experienced; these minute details say more than any number of words on a page can communicate.

Because the best experiences are those individually indulged and left unsaid.

Thoughts?