The quiet, distant hum of space is a phenomenal companion to introspection. The cool blues of the bulkhead and the energy efficient lights create a very low key atmosphere. All around, the walls and floors thrum with the sound of the engine.

Shepard’s cabin is uninviting and cold, but quietly sequestered away from the rest of the otherwise brighter, louder, and busier Normandy. Among the blue walls and gray sheets, Shepard and I are reading the codex, learning all there is to know about space, element zero, the numerous alien species that populate the galaxy as we know it.

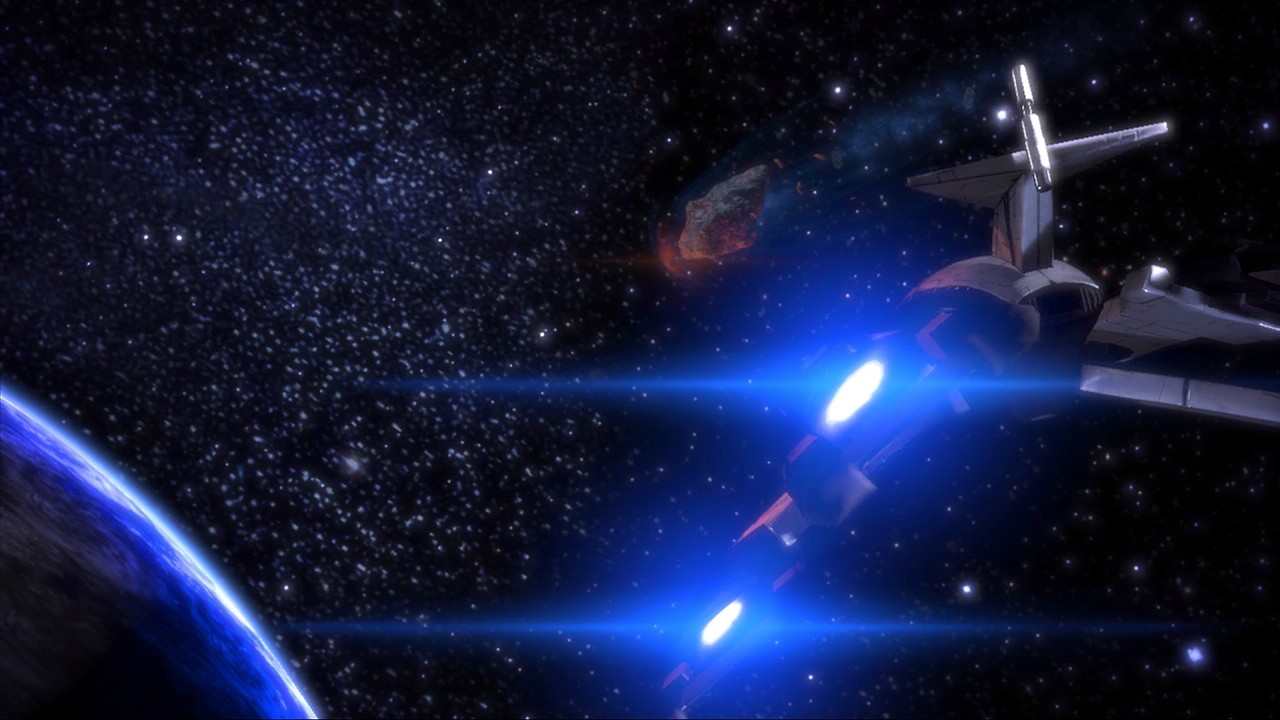

In Mass Effect, players climb in the boots of Commander Shepard, a human marine given the honor of being a Spectre, the galactic civilization’s premier peacekeeping police, and is sent out to stop a rogue agent. Shepard, however, is more concerned with a vision that suggests that the extinction of all of the sapient races could come at the hand of a massive, towering race of spacefaring creatures called the Reapers. Although the remainder of space is blissfully unaware of the danger, Shepard is not.

However, among the spartan halls of the captain’s quarters aboard the Normandy, I find the universe itself is far more fascinating than the the creatures who threaten it.

The codex is the game’s library of in-universe lore, a reference guide to several aspects of the Mass Effect universe broken down for easy reach and consumption. Each entry hosts a few paragraphs of information about the world. Several of the universe’s races are explored and explained, along with aspects of their physiology and culture. Technology, biotic abilities, historical accounts, and geopolitical curiosities are also detailed briefly throughout, painting a very beautiful picture of a universe brimmed with the opportunity for exploration.

Outside of the soft, well-spoken narrator of the codex, Mass Effect is a mystery-action thriller. The player combs the outer reaches of space, bumping into numerous clues about the Reapers, chasing the rogue spectre, and surviving the worst that the universe can dish out. The game is expansive, but selectively so, herding the player across a large galaxy more via menus than exploration, with terrestrial exploration confined to an awkward tank-buggy. When the action kicks off, the NPCs explode with sweeping dialog, gunfire, explosions, and biotic powers warping reality around them. Set pieces explode with gouts of lava, hailstorms of ice and snow, and an orbital bombardment.

While the events of Mass Effect are technically well-realized and heartfully delivered by a stellar voice cast, the universe never feels more alive than the opportunities implied in the brief yet nuanced descriptions of the in-game codex. The few paragraphs that make up the codex entries are the gateway to a larger galaxy. The menus and galactic charts successfully convey the sheer vastness of the Milky Way galaxy, but they still feel so remote, so alien. However, in the packed and crowded halls of the Citadel, aliens burst from the seems. They sit and discuss their lives, Shepard’s companions chat amiably in elevators and comment on their surroundings, and it all promises that unlike the cold, distant galactic chart, the universe is ballooning with intrigue and life.

I’ve spoken before about how games are just brief windows into their stories, and that their true depths lay forever out of view. While it’s often frustrating to see the opportunity for larger and deeper settings and stories, getting to spend time with these aspects is something altogether magical, and also one of the places where games can share familiar techniques with literature and film.

Mass Effect is an excellent game, and one of the few games I’ve played through repeatedly, but the actual play isn’t anything spectacular. The shooting is a little awkward and slow, doubly so when compared to its older brothers Mass Effect 2 and 3. The menus aren’t terribly ergonomic. The story beats are still forming, so a lot of the early parts of the game are built around a quagmire of exposition and information dumping. The scenery is littered with extras who have no dialog or player interaction whatsoever. The important characters themselves have some depth to them, but they’re buried away without much indication that they evolve more dialog as the story moves on. However, finally making time to settle in and indulge in their dialog is astounding.

What few named characters exist all have depth of personality and soul. Some are amiable and chatty, others spartan and mission-focused, some xenophobic, others infinitely curious, yet they’re all still empathetic enough to be worth speaking to again. Even those designed to be disagreeable. The world is absolutely filled to burst with information behind the curtain: new alien races, and new areas. Little stories about the companion’s families or histories galvanize me to right the wrongs that have plagued their past, and and I can’t help but wanting to invest just a little bit longer playing, just to see what’s next.

In part, some what what I find the most fun in gaming has very little to do with gaming itself, and a lot to do with humanity. I want to get behind my heroes. I want to wait with baited breath for every new detail, every little twist, every word of dialog or hint of depth sequestered behind something new. Some of the purest fun for the human mind comes from not just being a part of a narrative, but needing to be.

Games are typically expected to be very mechanical: jump to the platform, dodge the bullet, hit the beat, swing the sword. However, only observing value via mechanical “fun” discounts the reality that these mechanics are also elements of storytelling. They’re about getting to experience the highest moments of a character’s success, the tragic realities of a character’s failures, the impossible challenges and the joyous celebrations. Even when there are no named characters to follow, or no narrative arc built in, there are still stories to tell.

Anyone who’s played long sessions of Grand Theft Auto, Neptune’s Pride 2, or Rocket League has gotten to experience very complicated stories of success, betrayal, accidental success, and unfair loss. A game’s mechanics give the goings-on shape, the ability for stories to emerge naturally from the very act of play. These stories, like the mechanics themselves, are also an aspect of what makes play fun.

Fun means more than just shooting or stories.

So as Shepard and I lean back into what I can only imagine is a sparingly comfortable military cot, and the calm radiant voice of the codex tells me all about Volus breathing, I relish the moments of quiet learning between gunfire.

They’re more fun than most people realize.

Written for Critical Distance's Blogs of the Round Table under the "Pure Fun" theme. If this is up your alley, go give the other pieces a read.

Taylor Hidalgo would spend more time in the Spectres’ archives than the field if he ever enlisted. He can often be found in the untamed wilds of Twitter, or posting here on The Thesaurus Rex as well as on Haywire Magazine, Continue Play, and XPGain.

Thoughts?